Map of Reality

Lesson Launch Blog

By Dr. Paul E. Binford

Past President, Mississippi Council for the Social Studies

Wrong-Way Walker

I often workout at the Sanderson Center, an indoor athletic complex located on the campus of Mississippi State University and a short distance from my home. In this cavernous facility, there is a track on the upper floor with four basketball courts below.

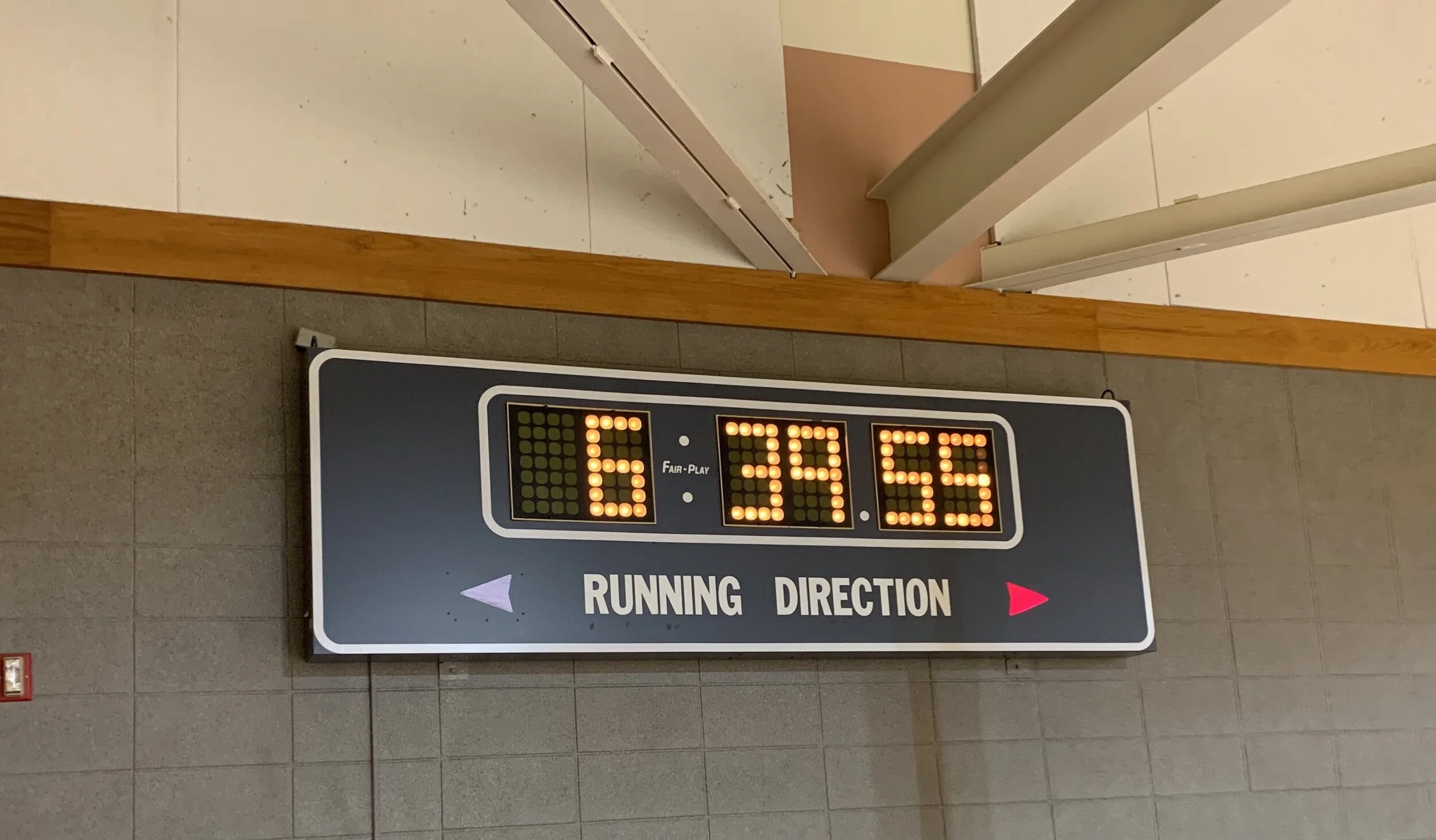

As you enter the track, there is a large, electronic—”basketball appearing”—scoreboard on the wall. This scoreboard, however, shows the time of day rather than the time remaining in the game.

It also has the words, “Running Direction” with an arrow on either side each pointing in opposite directions. The running direction on the track alternates each day, so one arrow is lighted while the other remains unilluminated. Upon entering the track, the first thing I do— along with scores of other walkers, joggers and runners—is check the directional arrow for the day.

While slowly making laps around the track, I am occasionally bemused by a patron, who enters the track and then proceeds to walk or run in the wrong direction (i.e., against the flow of traffic) for several laps. In spite of the fact that five, ten or, as many as, twenty other patrons are going in the opposite direction, this individual persists in matriculating around the track against the traffic flow. This, of course, requires the wrong-way walker to frequently change lanes and dodge runners to avoid collision, not to mention ignoring the incredulous glances of other patrons.

Typically, one sympathetic person will eventually point to the arrow sign, and the slightly embarrassed patron belatedly changes course.

Belated Comprehension

The social studies are replete with similar, but more consequential examples.

In describing the initial reactions to the Japanese attack on Pearly Harbor, historian Ian W. Toll observed that both civilians and military personnel were slow to comprehend the events they were witnessing.

In eyewitness accounts of December 7, 1941, this “belated comprehension—that an attack was unfolding—is repeated again and again.” (8) The cognitive process went like this:

Event: A plane approaches.

Eyewitness: ‘Why are those planes flying so low?’

Event: American ground-based antiaircraft guns fire at the intruder.

Eyewitness: ‘Why are the boys shooting at that plane?’

Events: A bomb drops.

Eyewitness: ‘What a stupid, careless pilot, not to have secured his releasing gear?’

Event: It explodes.

Eyewitness: ‘Somebody goofed big this time. They loaded live bombs on those planes by mistake.’

Event: As the plane turns upward, the Japanese “Rising Sun” insignia comes into view on the underside of the wings.

Eyewitness: ‘My … They’re really going all-out! They’ve even painted the rising sun on that plane!’

Event: An American ship explodes.

Eyewitness: ‘What kind of a drill is this?’ (8-9)

The Mirror

In the examples above, individuals encountered accumulating evidence that pointed to a clear conclusion. As simple as it may seem, this conclusion required each individual to change their map of reality and, then, behave differently:

“Oh, I’m walking the wrong way. I need to change direction.”

AND

“Can it be??? The Japanese are attacking Pearl Harbor! I need to take cover.”

From time-to-time, each one of us needs a mirror. Collecting evidence only becomes meaningful upon reflection. Then, we have the opportunity to make changes and course corrections. As painful as this can be for adults and, more specifically, teachers, this is exactly what we ask students to do every school day; it is a part of the learning process.

In fact, social studies content frequently offers this opportunity when taught skillfully.

A Final Note About Content:

Pacific Crucible: War at Sea in the Pacific, 1941-1942, by Ian W. Toll, is the first in a trilogy about the Pacific Theater during World War II. This volume chronicles the Empire of the Rising Sun as it reached its zenith with the attack on Pearl Harbor along with triumphs across the Pacific. These victories were, of course, short-lived. By the conclusion of 1942, the United States had stemmed the tide and was ready to go on the offensive.

Lesson Launch

The Lesson Launch welcomes your comments, feedback, and suggestions!

For more information about this Lesson Launch blog post, or if you are interested in arranging professional development or a speaking engagement, please contact the author at: theringoftruth@outlook.com.