Roll of Thunder: Intersections of Historical Fiction and Reality

Lesson Launch Blog

By Dr. Paul E. Binford

Past President, Mississippi Council for the Social Studies

This blog post is being jointly posted on Dr. Steve Bickmore’s YA Wednesday blog. Dr. Bickmore, a former colleague at LSU and a close friend, is an associate professor at the University of Nevada Las Vegas. He has a passion for and scholarly expertise in Young Adult literature.

The School Bus Incident

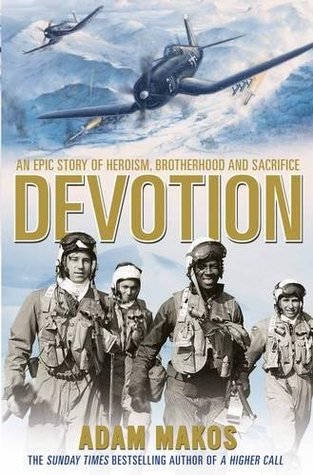

On a country road in southern Mississippi, Jesse Brown waited patiently to exact revenge.

In the distance, Jesse heard the unmistakable sounds of the school bus approaching. As he knew all too well, the rattling of the engine would soon be drowned out by noises more hostile—taunting, cursing, and spitting.

While Jesse anticipated the vehicle’s approach, the students on that bus would soon spot their next victim.

The year was 1939.

Jesse, the oldest son of an African American sharecropper, understood the routine. The bus would pass near him, the windows in the rear would be slid backward, and, then, angry faces would pop out followed immediately by a barrage of racial epithets and spittle.

Jesse instructed his two younger brothers to move off the road and into the field. Meanwhile, he grabbed a dried cornstalk about four feet long, shook off the dirt, and repositioned himself on the side of the road.

When the bus drew alongside, the rear windows retracted as expected. Jesse “choked up on the cornstalk like a bat. As the bus passed, he swung the cornstalk and smacked the first face that jutted from the windows” (pp. 28-29).

The ill-fated youngster squealed, and the boy’s friends yelled for the driver to stop the bus.

Adam Makos, the author of Devotion, finishes the story about the intrepid young Jesse Brown, who later became the first African American to serve as a U.S naval aviator:

A white man in suspenders stepped out, spit tobacco juice, and strode toward Jesse. The bus driver was older, yet he had broad shoulders and big fists . . . ‘What in the hell just happened here?’ the driver asked, his eyebrows narrowing.

‘Sir,’ Jesse said. ‘Every day when you pass us, those boys stick their heads out and spit on us.’

. . . ‘C’mon, let him have it!’ yelled the crying boy.

The driver studied Jesse from head to toe . . . ‘Well, that won’t happen anymore,’ the driver said.

The driver turned and strode back to the bus. (p. 29)

If this rural southern Mississippi school bus story sounds familiar, it might be because of the striking parallels to be found in Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry (ROT) by Mildred D. Taylor. In ROT, a menacing school bus torments the Logan children (pp. 12-15 & pp. 47-49) followed by sweet revenge (pp. 49-56). This is not to suggest that the former historical incident inspired the latter dramatic rendering. Rather, it is to recognize the credibility of the ROT’s historical infrastructure.

In case you have not read ROT, the story is about the Logan family during the Great Depression (1933) as told by one of the four children, Cassie. As an African American family living in rural Mississippi, the Logans confront the jarring inequalities of a racially segregated society.

Like many children, the Logan siblings assume the mantel of self-worth, but this clashes with the realities of living in the Jim Crow South. Some of the most poignant and revelatory moments in this novel occur when the Logan children confront racism (in various forms), and the ways they (and their parents) grapple with and process this hatred while maintaining a sense of familial pride and dignity. Sadly, the Logan children are introduced to these profound racial disparities through their schooling.

Two more (brief) examples of the intersections of historical fiction and reality, as illustrated by ROT’s portrayal of schooling, are the focus of the remainder of this blog post.

The School Buildings

The compelling contrast between the two segregated schools in ROT, Jefferson Davis County School (yes, there is a Jefferson Davis County in southern Mississippi) and The Great Faith Elementary and Secondary School (pp. 15-16) are buttressed by historical photographs from the Mississippi Department of Archives and History (MDAH), such as the one’s included here from Copiah County. To no surprise, the top photograph is a school for white children while the bottom image, as the archival record states, is:

Item: 2724

Antioch School

Album: Copiah County Schools-Negro

Copiah County, Mississippi

NOTE: The Antioch School is far from the most dismal example of a “Negro” school in Copiah County let alone the state of Mississippi.

In the early 1950s, the state government recognized the legal push for integration posed a serious threat to Mississippi’s segregated school system. Their response was to provide increased funding for “Negro” schools as a bulwark against this racial mixing. However, the first step was to document (i.e. photograph) the existing condition of public schools throughout the state.

For the reader of history and historical fiction, this inventory provides a treasure trove of evidence that “separate educational facilities [we]re inherently unequal.” While not all the inventory has been digitized (i.e., Jefferson Davis County’s school photographs are viewable only by traveling to MDAH in Jackson), enough county inventories are available digitally for teachers and students alike to view the obvious and disturbing disparites.

The School Textbooks

The opening chapter of ROT culminates with the Great Faith Elementary and Secondary School teachers distributing “new books” to their excited pupils (pp. 21-25). But the buildup belies the condition of these hand-me-down textbooks. The Logan children’s disappointment at receiving dilapidated books is exacerbated by an official label, found inside the front cover (p. 25), the last entry of which reads, in part :

Date of Issuance: September 1933. Condition of Book: Very Poor Race: nigra

The historical reality is Mississippi did not begin issuing free public school textbooks until 1940. However, individual school districts in the state did have the latitude to provide free school books pre-1940. Keep in mind, for most states the issuance of school textbooks—free of charge—began in earnest in the early to mid-twentieth century; this development was preceded and necessitated by compulsory school attendance laws.

One of the prevailing arguments against free public school textbooks, as Clyde J. Tidwell noted in 1928, was that “no satisfactory plan ha[d] been devised . . . for successfully fumigating or disinfecting textbooks." Needless to say, this concern over fumigation and disinfection had immigrant and African American households squarely in mind.

In the summer of 1940, the Mississippi State Textbook Purchasing Board was empowered to administer the newly enacted free public school textbook legislation. Regarding the distribution of textbooks to students, the board stipulated:

All books distributed under the provisions of the State Textbook Act shall have printed labels on both inside covers [emphasis mine]. On the labels shall be space provided for:

a. Name of pupil

b. Space for serial number of book and date

c. Name of school district and name of school

d. Name of County

e. Race [emphasis mine]

f. Condition of book when assigned and returned

In summary, ROT presents schooling in Depression Era Mississippi in a historically credible manner, which could readily serve as a representative example of the evils of Jim Crow for the nation at large. Furthermore, these intersections of fiction and reality provide ELA and Social Studies teachers and their students with rich opportunities for cross curricular teaching and learning.

The Lesson Launch welcomes your comments, feedback, and suggestions!

For more information about this Lesson Launch blog post, or if you are interested in arranging professional development or a speaking engagement, please contact the author at: theringoftruth@outlook.com.